Screening of Final Beneficiaries of Humanitarian Aid

7 September 2021Sanctions are a wide range of measures that aim to influence behaviour without involving the use of armed force. Sanctions can, however, also affect humanitarian action. This fact sheet looks at the requirement to screen final beneficiaries of humanitarian programmes, specifically in the context of the conflict in Syria.

Download PDF (opens in new window)

Institutional donors to humanitarian action, such as states and international organisations like the EU, frequently include restrictions and requirements in their funding agreements that aim to ensure that recipients of the funding comply with the counterterrorism measures and sanctions adopted by, or binding on, the donor.

One key objective of these restrictions is ensuring that funded activities do not benefit persons or entities designated under sanctions or counterterrorism measures.

The requirements are by no means uniform. They vary from donor to donor, context by context and, frequently, also with the recipient of the funding, depending on their status — whether they are UN agencies, other international organisations or non-governmental organisations. The nature of the funded activities is also a consideration, with programmes that entail the provision of cash being more tightly regulated.

States are not under a legal obligation to fund humanitarian programmes. But

if they do, they must not include provisions that are incompatible with international humanitarian law (IHL), or that prevent the recipient organisation from operating in accordance with humanitarian principles or medical ethics.

One of the most common provisions in funding agreements is a requirement to take measures to avoid that funds or other assets provided pursuant to the grant are made available directly or indirectly to designated persons or entities.

1. The nature of the obligation

Donors formulate the precise nature of this duty in different ways. Some impose what has been described as an ‘obligation of result’: recipients must ensure that assistance does not reach designated persons or entities. This is a high standard — probably unrealistically so — that many humanitarian actors are uncomfortable committing to. A preferable approach is imposing an ‘obligation of means’, that requires recipients to take ‘reasonable measures’ or ‘use their best endeavours’.

Some funding agreements specify the measures that must be taken to comply with this requirement. At other times it is left to recipients to choose the modalities for doing so. Most frequently, this is done by ‘screening’ a range of actors involved in the funded programmes to ensure they are not included in lists of persons or entities designated under relevant sanctions or counterterrorism measures.

2. What is ‘screening’? What is ‘vetting’?

Although the terms are frequently used interchangeably, screening must

be distinguished from vetting. Screening is carried out by humanitarian actors themselves. They check that persons or entities are not designated under UN, EU and other sanctions and counterterrorism measures. Various commercial programmes exist for doing this.

Vetting requires humanitarian actors to provide the identity information of relevant persons and entities to the donor, which will carry out the checks itself. Only a small minority of donors require vetting, and, even these, only in relation to grants for certain contexts. USAID, for example, currently requires vetting only for work in Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen and the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Applications for certain US government funding for operations in certain contexts require partner vetting — i.e., the provision of personal information of certain ‘key individuals’ in the organisation applying for funds, including principal officers of its governing board, directors, officers and other staff members with significant responsibilities for the management of the funded programme.

In some contexts, however, this has also included the vetting of final beneficiaries who receive more than a prescribed amount of assistance in cash or in kind or participate in training activities.

Vetting raises additional concerns to screening, including in terms of data protection and privacy in relation to the personal information that is provided

to the donor. Vetting can also undermine perceptions of the independence of humanitarian actors providing such information to the state donors. If the donor is a party to an armed conflict, the provision of personal information can also affect the perceived neutrality of humanitarian actors.

3. Why is screening of final beneficiaries problematic?

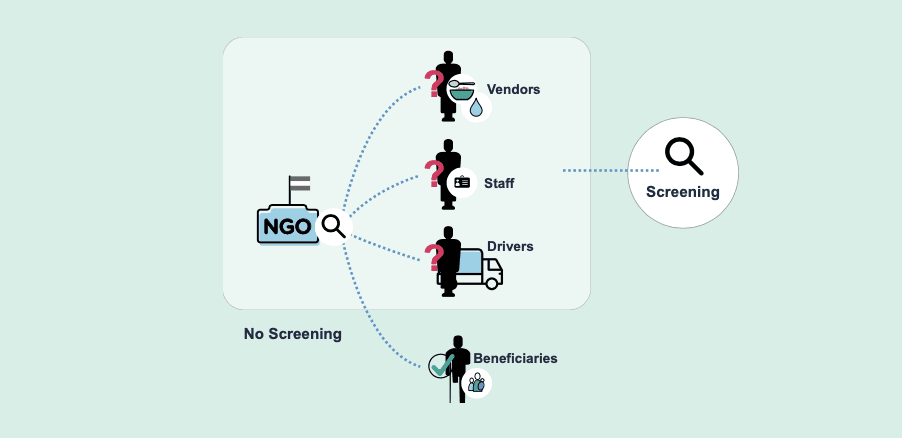

Screening is not problematic per se. It is a tool for identifying whether someone is on a list of designated persons. Screening of a range of persons and companies involved in the delivery of humanitarian programmes, including staff, sub-grantees, and contractors is an acceptable way of ensuring that funds or other assets are not provided to designated persons or entities in the course of humanitarian operations.

Screening can become problematic if it leads to exclusion of someone from humanitarian assistance that they have been determined as requiring. Once someone has been determined as in need of assistance on the basis of eligibility criteria developed by a humanitarian actor — which are frequently shared

with the donor — depriving them of this assistance would go further than what the underlying sanctions require and would also be incompatible with IHL and humanitarian principles.

4. Screening of final beneficiaries goes over and above what is required by sanctions

The purpose of screening requirements is to ensure compliance with sanctions and counterterrorism measures. But these very sanctions include exemptions allowing designated persons to access basic services, such as medical care, food and accommodation. This is a clear indication that sanctions must not deprive designated persons of essential services and goods.

The same holds true when these basic goods and services are provided in the form of humanitarian relief. In 2020, in a Guidance Note on EU sanctions, the European Commission expressly restated its well-established and consistent position that EU restrictive measures do not prohibit the provision of humanitarian assistance to those who have been determined to be in need thereof:

Should the Humanitarian Operators vet [sic] the final beneficiaries of humanitarian aid?

No, [a]ccording to International Humanitarian Law, Article 214(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, independence and neutrality, humanitarian aid must be provided without discrimination. The identification as an individual in need must be made by the Humanitarian Operators on the basis of these principles. Once this identification has been made, no vetting [sic] of the final beneficiaries is required.

Moreover, sanctions and the majority of counterterrorism measures prohibit

making funds or assets available to designated persons. They do not cover training. Requirements to screen and thus potentially exclude participants in training programmes also go beyond the underlying sanctions.

5. Screening of final beneficiaries is incompatible with IHL and humanitarian principles

Under IHL everyone — civilian and wounded or sick fighter — is entitled to the medical care required by their condition, with no discrimination other than on medical grounds. Everyone deprived of their liberty — civilian and fighter — is entitled to food, water and clothing. Even when not deprived of their liberty civilians are entitled to objects indispensable to their survival, including food, water, medical items, clothing and bedding. If the belligerent with control of civilians is unable or unwilling to provide these, humanitarian relief operations may be conducted to provide these goods.

With regard to all these entitlements, once a person has been determined as being in need of the particular type of assistance, the humanitarian principle of impartiality requires it to be provided with no discrimination other than on the basis of greatest need. Depriving people of the assistance to which they are entitled, on the ground that they are designated under sanctions or counterterrorism measures, would violate IHL.

The position is different for fighters who are not hors de combat. They do not have the same entitlement as civilians to other objects indispensable to their survival, such as food. But individuals can be designated for a broad range of reasons, many of which would not affect a person’s status as civilian under IHL. There is thus no equivalence between being a fighter, and thus not entitled to benefit from certain types of humanitarian relief, and being designated. Screening risks, in this case too, to deprive individuals of the humanitarian relief they are entitled to under IHL.

More operationally, the eligibility criteria developed by humanitarian actors and their implementation in practice go a long way in ensuring that humanitarian assistance is not provided to fighters.

6. The state of play

While humanitarian organisations have been willing to screen staff, sub-grantees, contractors and vendors, they have drawn a ‘red line’ at screening final beneficiaries.

On the whole this red line has been accepted by donors to humanitarian action, including the EU, the US and other key donors. However, it is now being challenged by a number of developments.

Although the US has frequently stated that it does not require screening of final beneficiaries of the programmes it funds, in practice its approach is not quite so clear cut.

In contexts subject to enhanced partner vetting, recipients of USAID funding must vet — i.e., provide USAID with the personal information of — individual participants in training programmes funded with the grant, and recipients of cash payments above a particular amount.

More problematically, in recent years funding agreements concluded with certain humanitarian actors in contexts where groups designated as terrorist by the US are operative, including Boko Haram in Nigeria and ISIL in Syria and Iraq, have required seeking prior authorisation from USAID before providing assistance to individuals whom the recipient ‘affirmatively knows’ to have been ‘formerly affiliated’ with these groups ‘as combatants or non-combatants’.

USAID has not provided guidance as to what constitutes former affiliation with a designated group. This is likely to be a larger group of individuals than those who are designated, so people who are not even designated could potentially be excluded from humanitarian programmes on this basis.

Admittedly, the requirement neither requires recipients of funding to provide USAID with the personal data of the persons in question, nor does it automatically preclude assistance from being provided to them. It is for USAID to decide what the consequences of any notification are. Nonetheless a very real risk exists that this requirement may exclude individuals from life-saving assistance, including measures aimed at treating and reducing the spread of COVID-19. Not providing medical assistance — even just pending authorisation — would violate IHL and humanitarian principles, and be contrary to medical ethics.

There have also been problematic developments at EU level. Since 2018, new grant agreements concluded by departments of the European Commission other than ECHO have started requiring the screening of final beneficiaries of funded programmes.

The department within an organisation that provides the funding does not affect the position outlined above. What matters is the context in which the funded activities are being conducted. Is it one where IHL applies, or to which humanitarian principles are otherwise relevant? And the nature of the funded activities. Both must be determined on the basis of the facts on the ground and not the institutional identify of the donor.

There has been significant pushback to the inclusion of this requirement, most notably in relation to activities that are being conducted in conflict settings, such as Syria. Some NGOs terminated a grant that required the screening of final beneficiaries and returned the funds. Others successfully argued that the requirement should only apply to the parts of the grant that related to cash-based activities, as only these were covered by the EU sanctions and not parts related to training. They returned the portion of the grant related to cash-assistance and implemented the other activities without screening final beneficiaries.

Adopting these principled positions is essential to maintaining the red line. It is nonetheless regrettable that it was necessary to return the funds as this left individuals without the assistance they needed, as determined by the humanitarian actors on the ground.

Header Photo: Food assistance beneficiaries carry aid packages in Sinjar village, southern rural Idlib in Syria. © UNICEF/Sanadiki